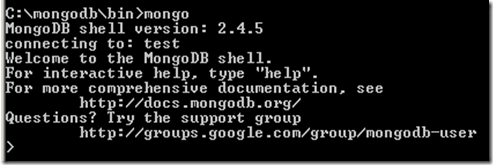

In the previous post we explored the basics of MongoDB. In this post we going to dig deeper in MongoDB.

Indexing

Whenever a new collection is created, MongoDB automatically creates an index by the _id field. These indexes can be found in the system.indexes collection. You can show all indexes in the database using db.system.indexes.find() . Most queries will include more fields than just the _id, so we need to make indexes on those fields.

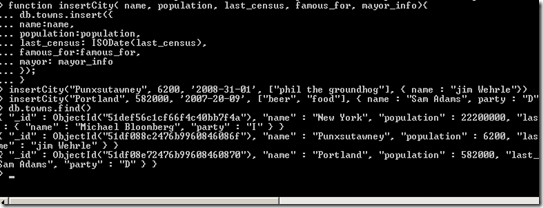

Before creating more indexes, let’s see what is the performance of a sample query without creating any indexes other than the automatically created one for _id. Create the following function to generate random phone numbers.

function (area,start,stop) {

for(var i=start; i < stop; i++) {

var country = 1 + ((Math.random() * 8) << 0);

var num = (country * 1e10) + (area * 1e7) + i;

db.phones.insert({

_id: num,

components: {

country: country,

area: area,

prefix: (i * 1e-4) << 0,

number: i

},

display: "+" + country + " " + area + "-" + i

});

Run the function with a three-digit area code (like 800) and a range of seven digit numbers (5,550,000 to 5,650,000)

populatePhones( 800, 5550000, 5650000 )

Now we expecting to see a new index created for our new collection.

> db.system.indexes.find()

{ "v" : 1, "key" : { "_id" : 1 }, "ns" : "newdb.towns", "name" : "_id_" }

{ "v" : 1, "key" : { "_id" : 1 }, "ns" : "newdb.countries", "name" : "_id_" }

{ "v" : 1, "key" : { "_id" : 1 }, "ns" : "newdb.phones", "name" : "_id_" }

Now let’s check the query without an index. The explain() method is used to output details of a given operation and can help us here.

> db.phones.find( { display : "+1 800-5650001" } ).explain()

{

"cursor" : "BasicCursor",

"isMultiKey" : false,

"n" : 0,

"nscannedObjects" : 100000,

"nscanned" : 100000,

"nscannedObjectsAllPlans" : 100000,

"nscannedAllPlans" : 100000,

"scanAndOrder" : false,

"indexOnly" : false,

"nYields" : 0,

"nChunkSkips" : 0,

"millis" : 134,

"indexBounds" : {

},

"server" : "ESOLIMAN:27017"

}

Just to make things simple, we will look at the millis field only which gives the milliseconds needed to complete the query. Now it is 134.

Now we going to create an index and see how it improves our query execution time. We create an index by calling ensureIndex(fields,options) on the collection. The fields parameter is an object containing the fields to be indexed against. The options parameter describes the type of index to make. On production environments, creating an index on a large collection can be slow and resource-intensive, you should create them in off-peak times. In our case we going to build a unique index on the display field and we will drop duplicate entries.

> db.phones.ensureIndex(

... { display : 1 },

... { unique : true, dropDups : true }

... )

lets try explain() of find() and see the new value for millis field. Query execution time improved, from 134 down to 16.

> db.phones.find( { display : "+1 800-5650001" } ).explain()

{

"cursor" : "BtreeCursor display_1",

"isMultiKey" : false,

"n" : 0,

"nscannedObjects" : 0,

"nscanned" : 0,

"nscannedObjectsAllPlans" : 0,

"nscannedAllPlans" : 0,

"scanAndOrder" : false,

"indexOnly" : false,

"nYields" : 0,

"nChunkSkips" : 0,

"millis" : 16,

"indexBounds" : {

"display" : [

[

"+1 800-5650001",

"+1 800-5650001"

]

]

},

"server" : "ESOLIMAN:27017"

}

Notice the cursor changed from a Basic to a B-tree cursor. MongoDB is no longer doing

a full collection scan but instead walking the tree to retrieve the value.

Mongo can build your index on nested values: db.phones.ensureIndex({ "components.area": 1 }, { background : 1 })

Aggregations

count() counts the number of matching documents. It takes a query and returns a number.

> db.phones.count({'components.number': { $gt : 5599999 } })

100000

distinct() returns each matching value where one or more exists.

> db.phones.distinct('components.number', {'components.number': { $lt : 5550005 } })

[ 5550000, 5550001, 5550002, 5550003, 5550004 ]

group() groups documents in a collection by the specified keys and performs simple aggregation functions such as computing counts and sums. It is similar to GROUP BY in SQL. It accepts the following parameters

- key – Specifies one or more document fields to group by.

- reduce – Specifies a function for the group operation perform on the documents during the grouping operation, such as compute a sum or a count. The aggregation function takes two arguments: the current document and the aggregate result for the previous documents in the group.

- initial – Initializes the aggregation result document.

- keyf – Optional. Alternative to the key field. Specifies a function that creates a “key object” for use as the grouping key. Use the keyf instead of key to group by calculated fields rather than existing document fields. Like HAVING in SQL.

- cond – Optional. Specifies the selection criteria to determine which documents in the collection to process. If you omit the cond field, db.collection.group() processes all the documents in the collection for the group operation.

- finalize – Optional. Specifies a function that runs each item in the result set before db.collection.group() returns the final value. This function can either modify the result document or replace the result document as a whole.

> db.phones.group({

... initial : { count : 0 },

... reduce : function(phone, output) { output.count++; },

... cond : { 'components.number' : { $gt : 5599999 } },

... key : { 'components.area' : true }

... })

[

{

"components.area" : 800,

"count" : 50000

},

{

"components.area" : 855,

"count" : 50000

}

]

The first thing we did here was set an initial object with a field named count set to 0—fields created here will appear in the output. Next we describe what to do with this field by declaring a reduce function that adds one for every document we encounter. Finally, we gave group a condition restricting which documents to reduce over.

Server-Side Commands

All queries and operations we did till now, execute on the client side. The db object provides a command named eval(), which passes the given function to the server. This dramatically reduces the communication between client and server. It is similar to stored procedures in SQL.

There is a also a set of prebuilt commands that can be executed on the server. Use db.listCommands() to get a list of these commands. To run any command on the server use db.runCommand() like db.runCommand({ "count" : "phones" })

Although it is not recommended, you can store a JavaScript function on the server for later reuse.

MapReduce

MapReduce is a framework for parallelizing problems. Generally speaking the parallelization happens on two steps:

- "Map" step: The master node takes the input, divides it into smaller sub-problems, and distributes them to worker nodes. A worker node may do this again in turn, leading to a multi-level tree structure. The worker node processes the smaller problem, and passes the answer back to its master node.

- "Reduce" step: The master node then collects the answers to all the sub-problems and combines them in some way to form the output – the answer to the problem it was originally trying to solve.

To show the MapReduce framework in action, let’s build on the phones collections that we created previously. Let’s generate a report that counts all phone numbers that contain the same digits for each country.

First we create a helper function that extracts an array of all distinct numbers (this step is not a MapReduce step).

> distinctDigits = function(phone) {

... var

... number = phone.components.number + '',

... seen = [],

... result = [],

... i = number.length;

... while(i--) {

... seen[+number[i]] = 1;

... }

... for (i=0; i<10; i++) {

... if (seen[i]) {

... result[result.length] = i;

... }

... }

... return result;

... }

> db.eval("distinctDigits(db.phones.findOne({ 'components.number' : 5551213 }))")

[ 1, 2, 3, 5 ]

Now let’s find find distinct numbers of each country. Since we need to query by country later, we will add the distinct digits array and country as compound key. For each distinct digits array in each country, we will add a count field that hold the value 1.

> map = function() {

... var digits = distinctDigits(this);

... emit( { digits : digits, country : this.components.country } , { count : 1 } );

... }

The reducer function will all these 1s that have been emitted from the map function.

>reduce = function(key, values) {

... var total = 0;

... for(var i=0; i<values.length; i++) {

... total += values[i].count;

... }

... return { count : total };

... }

Now it is time to put all pieces together and start the whole thing (the input collection, map function, reduce function, output collection).

> results = db.runCommand({

... mapReduce : 'phones',

... map : map,

... reduce : reduce,

... out : 'phones.report'

... })

{

"result" : "phones.report",

"timeMillis" : 21084,

"counts" : {

"input" : 200000,

"emit" : 200000,

"reduce" : 48469,

"output" : 3489

},

"ok" : 1

}

Now you can query the output collection like any other collection

> db.phones.report.find()

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 ], "country" : 1 }, "value" : { "count" : 37 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 ], "country" : 2 }, "value" : { "count" : 23 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 ], "country" : 3 }, "value" : { "count" : 17 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 ], "country" : 4 }, "value" : { "count" : 29 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 ], "country" : 5 }, "value" : { "count" : 34 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 ], "country" : 6 }, "value" : { "count" : 35 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 ], "country" : 7 }, "value" : { "count" : 33 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 32 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 5 ], "country" : 1 }, "value" : { "count" : 5 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 5 ], "country" : 2 }, "value" : { "count" : 7 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 5 ], "country" : 3 }, "value" : { "count" : 3 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 5 ], "country" : 4 }, "value" : { "count" : 6 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 5 ], "country" : 5 }, "value" : { "count" : 5 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 5 ], "country" : 6 }, "value" : { "count" : 10 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 5 ], "country" : 7 }, "value" : { "count" : 5 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 5 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 7 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 ], "country" : 1 }, "value" : { "count" : 95 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 ], "country" : 2 }, "value" : { "count" : 104 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 ], "country" : 3 }, "value" : { "count" : 108 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 ], "country" : 4 }, "value" : { "count" : 113 } }

Type "it" for more

or

> db.phones.report.find({'_id.country' : 8})

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 32 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 5 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 7 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 127 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 28 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 27 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 9 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 29 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 10 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 7 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 9 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 8 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 4, 5 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 3 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 121 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 25 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 27 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 9 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 17 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 4, 5, 7 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 4 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 4, 5, 8 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 4 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 4, 5, 9 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 7 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 5 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 14 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 5, 6 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 162 } }

{ "_id" : { "digits" : [ 0, 1, 2, 5, 6, 7 ], "country" : 8 }, "value" : { "count" : 95 } }

Type "it" for more

The unique emitted keys are under the field _id, and all of the data returned from the reducers are

under the field value. If you prefer that the mapreducer just output the results, rather than outputting to a collection, you can set the out value to { inline : 1 }, but bear in mind there is a limit to the size of a result you can output (16 MB).

In some situations you may need to feed the reducer function’s output into another reducer function. In these situations we need to carefully handle both cases: either map’s output or another reduce’s output.

MongoDB have so many features that we didn’t even mentioned here. In later posts will continue working on them.